“If you repeat a lie often enough, it becomes the truth”, is a quote typically ascribed to Josef Goebbels, Reich Minister of Propaganda of Nazi Germany. The irony of this is that according to Professor Randall Bytwerk, Goebbels never said it. Yet there are over 500,000 web pages and twenty published books that attribute, without a citation of a source, this quote to him. This underscores the truth of the statement, specifically because of it’s innate historical inaccuracy. How many “experts” will continue to repeat this incorrect assertion because they are too dull, uninformed, disinterested, or biased, to care whether it’s correct? https://www.bytwerk.com/gpa/falsenaziquotations.htm

When researching the parkways built by Robert Moses, there are a considerable number of sources that contend that he purposely built the bridge overpasses too low so that the minorities of New York City wouldn’t be able to access Long Island’s State Park system, specifically, Jones Beach. There are a number of easily discovered materials on the internet that show that buses could always access the Park, such as the below 1937 Bus Schedule from Flushing:

Jones Beach opened August 4, 1929. The 1930 census shows that the demographic breakdown of New York City’s population of 6,930,446 was 95.08% white and 4.73% black. It wasn’t until 1960, thirty years after the Park’s opening day, that the white population of the city fell below 90% to 85.33%. If there had been a goal to build low bridges in order to keep out bus bound minorities, then Moses would have needed a crystal ball as part of his planning toolkit. Not to mention all of the white denizens of the five boroughs that he supposedly, purposely would have excluded until the minority populations of the city had grown large enough.

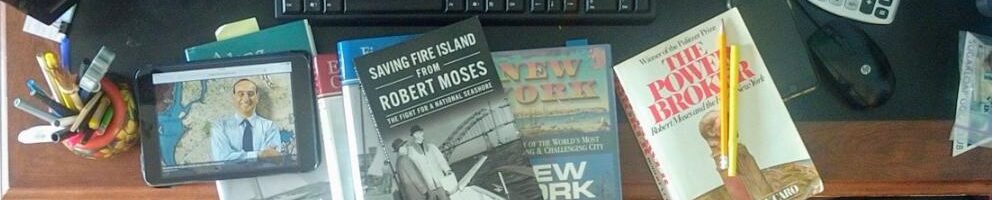

I first heard the low bridge tale when one of my friends was told the story by his father, who I can only assume recently, read “The Powerbroker”, he then told a group of us. We were all in our late teens and had previously ridden the bus to the beach. To say the least we were collectively puzzled. Comments popped up such as, “maybe the buses couldn’t get there during the early years of the park?” or “did they use smaller vans until they fixed the bridge problem?”. The assumption was that since it was written in a book, it had to be true, so we were then left to try to figure out how both the idea and our shared realities could coexist.

In the particular case of our neighborhood, it wasn’t unusual, in a one car household, for the carless parent or older kids accompanied sometimes by their younger siblings to get to the beach by catching the Massapequa loop bus to Massapequa Park train station where they would transfer to another bus that would stop at Massapequa and Seaford train stations and continue on to Jones Beach. This wasn’t unique, at that time, Long Island had a significant number of mass transit bus routes and destinations.

Never Let The Truth Get In The Way Of A Good Story

So how did this get started and continue to be perpetuated? By individuals repeating a story that they’ve heard or read, but who have also never taken the bus to Jones Beach. Probably the best example of this was an article in Curbed by Michael Adno entitled “Robert Moses’s Jones Beach”, in it he writes,

“Above the entrance to the tower, a frieze of the New York state seal watches over the Wantagh Parkway’s final stretch. About 1,500 feet from the base of the seal, the figures of Liberty and Justice look out toward a low stone bridge at the terminus of the Wantagh Parkway. The low-lying bridge is one of hundreds that dot the parkways along the island. Those low bridges might have been Moses’ most maligned misdeed, one that superseded legislation, authorities, or commissions, and the thing that has kept public transportation from Jones Beach since its opening on August 4, 1929.

Later he goes on to write that “Today, the route to Jones Beach via public transportation is arduous and time-consuming. From Manhattan or the boroughs, make your way out to Babylon via the Long Island Rail Road. During the summer, buses run from there to Jones Beach supposedly every 30 minutes, but most visitors without cars hop cabs to the beach from the South Shore at $25 to $30. “https://ny.curbed.com/2017/6/21/15838436/robert-moses-jones-beach-history-new-york-city

Thank goodness Mr. Adno only works as a journalist and not as a NYSP tourism director or even at the MTA information desk at Penn Station. There is no bus from Babylon to Jones Beach State Park. It may have been an unfortunate misadventure, for any individuals who might have made the trip to Babylon to go to Jones Beach, on this article’s advice. Hopefully they figured out that a bus does travel from Babylon to Robert Moses State Park.

To illustrate the nature of the problem, buses run from the Freeport train station to the beach (N88) and from Hicksville through Wantagh train stations also to the beach (N87). Did the author of the article investigate these facts? No, because there’s no need to look for something if you don’t believe it exists. Frankly it seems that there have been more earnest attempts to find Big Foot or The Loch Ness Monster than many scholars and writers have endeavored in order to find the “elusive” bus to Jones Beach. By the way, the one way fare by NICE bus is $2.75 and Metrocards are accepted. At the very least, for your economic health, don’t take a $30 cab ride.

Now it might be said that a freelance writer trying to sell a story is probably not the best source for historical accuracy. Let’s consider another article that constantly tops google searches of “Robert Moses Parkways”, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-07-09/robert-moses-and-his-racist-parkway-explained This article has been penned by Thomas J. Campanella PhD. He is a faculty member at Cornell University who received a BS in Environmental Studies from SUNY, a Masters in Landscape Architecture from Cornell, and a PhD from MIT where his thesis was based on the History of Urbanism and Landscape, College of Architecture and Planning.

In the article, Doctor Campanella makes similar errors seen in countless other works concerning Mr. Moses and his parkways. He takes a narrow view and looks to Caro as his source, as a result the findings typically reflect the perspectives presented in “The Powerbroker”. His article states that:

““Legislation can always be changed,” (Sid) Shapiro told Caro; “It’s very hard to tear down a bridge once it’s up.” So did Moses use cement and stone to effectively backstop the vehicular exclusion policy, insuring that the Southern State could never be used to schlep busloads of poor folk to Jones Beach?

“I decided to test this by comparing bridge clearances on the Southern State to those on the three earlier Westchester roads. Mengisteab Debessay, an engineer with New York State Department of Transportation, directed me to a database of bridge clearances statewide used for route planning—thus sparing me a time-consuming windshield survey. A measure of the minimum height between the pavement and the bottom of the overpass structure, clearances tend to change only modestly with road resurfacings. Unless a bridge is upgraded or replaced, clearances remain stable over time.

Limiting my search to only those arched stone or brick-clad structures in place or under construction when Moses began work on the Southern State, I recorded clearances for a total of 20 bridges, viaducts and overpasses: 7 on the Bronx River Parkway (completed in 1925); 6 on the initial portion of the Saw Mill River Parkway (1926) and 7 on the Hutchinson River Parkway (begun in 1924 and opened in 1927). I then took measure of the 20 original bridges and overpasses on the Southern State Parkway, from its start at the city line in Queens to the Wantagh Parkway, the first section to open (on November 7, 1927) and the portion used to reach Jones Beach. The verdict? It appears that Sid Shapiro was right.

Overall, clearances are substantially lower on the Moses parkway, averaging just 107.6 inches (eastbound), against 121.6 inches on the Hutchinson and 123.2 inches on the Saw Mill. Even on the Bronx River Parkway—a road championed by an infamous racist, Madison Grant, author of the 1916 best seller The Passing of the Great Race—clearances averaged 115.6 inches. There is just a single structure of under eight feet (96 inches) clearance on all three Westchester parkways; on the Southern State there are four.”

Let’s first consider some methodological errors and correct them.

In regard to the statement “clearances are substantially lower on the Moses parkway, averaging just 107.6 inches (eastbound)”. As noted on http://www.nycroads.com/roads/southern/ “Beginning in 1954, and continuing through 1963, construction crews built a new roadway separated from the original by a variable median. However, it was not as simple as adding a roadway parallel to the existing one. Engineers used the original underpasses for the westbound lanes in some locations and the eastbound lanes in others, and in the process gave the parkway a slightly straighter alignment.”

This would demonsrate that some of Dr. Campanella’s “eastbound” bridges were constructed in the mid 1920s, while others were built considerably later.

Additionally, the utilization of “a database of bridge clearances statewide used for route planning—thus sparing (him) a time-consuming windshield survey”, underscores the problems with this approach, in that it provides no context but the present. It also dovetails with the mistaken presumption that “clearances tend to change only modestly with road resurfacings. Unless a bridge is upgraded or replaced, clearances remain stable over time.” When Robert Moses began construction on the Southern State Parkway, it was an undivided road with two 10 and a half foot lanes in each direction for a 42 foot total roadbed width. Since that time it has undergone substantial widening and other modifications. Widening a road under an arched bridge will reduce current clearances compared to the original design.

When studying a system that’s almost 100 years old that has undergone extensive changes in a county that had an explosive population growth of almost 12x (120,120 in 1920 to 1,428,080 in 1970) over that time, it’s important to consider all factors that shaped the current conditions of the parkway.

Although it does seem ridiculous that a considerable number of “experts” focus on the height of a bridge rather than whether it serves the “racist” function they claim it does.

Bethpage State Parkway

I recently made a “windshield survey” of Bethpage State Parkway which was completed in 1936. Construction of the thoroughfare began in 1934; it also accesses a state park. Unlike many of the other parkways, this one hasn’t undergone as many changes. There had been plans to extend it south to Merrick Road and north to a terminus at Caumsett State Park. If these extensions had occurred the road would have been extensively modified. A fun fact is that since this parkway wasn’t extended, the Long Island Expressway doesn’t have an exit 47, which would have been the interchange of these two roads. Ultimately, the passage of time and the construction of Seaford Oyster Bay Expressway left Bethpage Parkway close to its original design.

From south to north, these bridges’ clearance signs are marked as 12’5″, 11’2″, 11’10”, and 9’9″. When these are converted to inches, these heights are 149″, 134″, 142″, and 117″. The double lined center median is about two feet wider than originally constructed, while the two lanes are at least three feet wider combined, and the shoulder has been extended as well. Not to mention that the second and fourth bridges have entrance/exit lanes placed beneath them. Many of these changes took place since the late 1970s when, like all of the parkways, the NYSDOT took over modernizing the roads to current standards.

Of particular note is the fourth bridge as it best illustrates the effects of widening a road under an arch. It has the lowest height at 9’9″, but also has two travel lanes and an exit lane.

The significance of this particular road, was that it was completed within 10 years of the Southern State’s connection to Wantagh Parkway and it also provided access to a State Park, yet the heights are comparable with the “racially neutral” Hutchinson, Saw Mill, and Bronx River Parkways of Dr. Campanella’s study. Was Mr. Moses no longer a racist? Did he not care if the, for the most part, small minority populations of New York City accessed Bethpage Park while staying away from Jones Beach?

When these parkways were being planned and built, it was happening in a rapidly changing enviroment, and these roads were evolving as such. This is best illustrated by Sidney M. Shapiro (yes, the same guy mentioned in the Campanella article), the Assistant Chief Engineer of the Long Island State Park Commission when he said upon the connection of the Northern State Parkway to the system, “The Northern State-Wantagh State Parkway is the final link in a forty-three mile express road from the Triborough Bridge to Jones Beach. Those parkways built ten years ago for example are in some respects obsolete… “. (NYT 11/15/1936, “New Highways Across Long Island To Link North And South Shores”) If these were his views in the mid-1930s, how “obsolete” might some aspects of these parkways be 20, 40, or 90 years later?

As an aside, I also find it difficult to believe that an experienced engineer such as Shapiro couldn’t come up with a solution to a bridge too low other than to demolish it. If necessary, the road bed could be easily and cheaply excavated in order to lower it and consequently increase the clearance.

Then And Now

Here’s a 1933 photo looking south from the bridge mentioned in Mr. Adno’s article.

Let’s compare that with a more modern image.

Notice any differences? Number of lanes, lane and overall roadbed widths….

Seeing Is Believing

The below video shows the bus ride from Wantagh to Jones Beach, skip ahead to 9:55, the bus passes under the bridge referenced in Mr. Adno’s article. Apparently this “most maligned misdeed” isn’t some neferious monument to racism, being looked over by “Liberty”, because technically “Justice” is blindfolded and would have to take Liberty’s word for it, but merely a bridge passed under by hundreds of millions on the way to a day at the beach that Robert Moses had built for them.

Another interesting point that refutes the “racist low bridge” yarn, is that for a Master Builder, known for his exacting nature, who was supposedly intent on physically stopping bus traffic on his parkways by building low bridges, he failed miserably at that alleged goal by doing the exact opposite. The traffic route of bus stops at the West Bathhouse, Central Mall, East Bathhouse, and Zach’s Bay illustrate that the park was specifically designed for mass transit.

All sorts of tall vehicles that belong and some that don’t traverse the parkways. It’s normally the ones that don’t belong that get into trouble. In 2018, a bus which wasn’t using a commercial GPS, left JFK Airport enroute to a mall in Huntington N.Y. While the height limit for intercity buses is twelve feet, most models are closer to eleven. The route traveled took both The Belt and Southern State Parkways. According to the New York State Police investigation, the bus progressed under 16 bridges before striking one at Eagle Avenue, Exit 18 in Lakeview. State Police Maj. David Candelaria said that the bus would have been able to pass safely through the overpasses, “if you generally stay in the middle lane.” https://projects.newsday.com/long-island/parkway-bridge-sensors/

Major Candelaria is correct. Most people look at the clearance signs not realizing that the height is measured from the lowest point of the arch. Also, the DOT often tries to build a margin for error into this limit. As an example, the Fletcher Avenue bridge on Southern State Parkway lists a nominal clearance of 7’8″, which is only one inch higher than the Eagle Avenue Bridge, yet the bus in 2018 cleared it. https://ronslog.typepad.com/ronslog/2018/04/low-clearance-on-new-york-parkways-results-in-bus-crash.html

It’s not unusual for school buses to be on Long Island’s Parkways, the other day, I had followed (westbound to Wantagh Avenue) a school bus as it passed through several bridges:

In general these buses are roughly 10′ in height, but it doesn’t appear that this bus is anywhere near these overpasses.

Imagine how ridiculous it would be if “low bridges” prevented emergency vehicles from being able to respond to accidents.

Or snowplows from clearing the parkway:

The Snowball Effects Of Academic Carelessness

In April of 2015, Sarah Schindler J.D., wrote an article that appeared in the Yale Law Journal entitled “Architectural Exclusion: Discrimination and Segregation Through Physical Design of the Built Enviroment.” Dr. Schindler was awarded both her Bachelor and Juris Doctor degrees with summa cum laude designations from the University of Georgia and currently is a law professor at the University Of Maine School Of Law. https://www.yalelawjournal.org/article/architectural-exclusion

In the article she wrote, “Robert Moses was known as the “Master Builder” of New York. During the time that he was appointed to a number of important state and local offices, he shaped much of New York’s infrastructure, including a number of “low-hanging overpasses” on the Long Island parkways that led to Jones Beach. According to his biographer, Moses directed that these overpasses be built intentionally low so that buses could not pass under them.This design decision meant that many people of color and poor people, who most often relied on public transportation, lacked access to the lauded public park at Jones Beach.

Later in the article she continues, “A paradigmatic example of architectural exclusion through physical barriers is Robert Moses’s Long Island bridges that were mentioned in the Introduction to this Article. Moses set forth specifications for bridge overpasses on Long Island, which were designed to hang low so that the twelve-foot tall buses in use at the time could not fit under them. “One consequence was to limit access of racial minorities and low-income groups”—who often used public transit—”to Jones Beach, Moses’s widely acclaimed public park. Moses made doubly sure of this result by vetoing a proposed extension of the Long Island Railroad to Jones Beach.” Moses’s biographer suggests that his decision to favor upper- and middle-class white people who owned cars at the expense of the poor and African-Americans was due to his “social-class bias and racial prejudice.”

Instead of garnering support to pass a law banning poor people or people of color from the places in which he did not want them—which, if the intent were clear, would not be permissible today—Moses used his power as an architect to make it physically difficult for certain individuals to reach the places from which he desired to exclude them. Although in this situation, there was at least anecdotal evidence of the architect’s intent, that sort of evidence is often not available.“

Based on the points raised earlier in this post, we can see that the author of this article made, what’s becoming an all too common error. She used Caro as her primary source and as a result produced research built on a faulty foundation and perpetuated an easily disproved narrative. What is occuring among this elite class of well credentialed scholars, politicians, policy makers, etc. is an inane game of telephone in which flawed information is repeated and further distorted until it ultimately arrives at defective conclusions. The deleterious effects of this lack of professional accuracy only serves to hinder authentic intellectual research.

As an example, Schindler discusses how Moses “vetoed” a Long Island Rail Road spur to Jones Beach to ensure that those not wealthy enough to own a car would be kept out. In reality, the goal of Jones Beach was to give visitors a resort experience at a public park that was accessible by primarily bus driven mass transit. One only needs to look to Coney Island, The Rockaways, and Long Beach to witness the sprawl that a beach rail line creates. Not to mention what happens to those lines when they fall into disuse, such as the abandoned Rockaway Beach Branch that’s been out of service since 1962.

abandonednyc.com

Additionally, Moses wouldn’t try to pass a law “banning poor people”, because his success was directly tied to the popularity of his projects. It borders on moronic to think that a progressive, ambitious, hard-working public servant would risk his future by sabotaging these undertakings in order to advocate a bigoted agenda. Although I would defer to the law professor to determine, even in the age of Plessy v. Ferguson, how a separate but equal Jones Beach could be constructed, or the necessary mechanisms to ensure that the more impoverished classes would be properly excluded?…laminated tax returns for beach entry…?

It’s important to consider that these critics are more likely to spend their summers on the beaches of Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and the Hamptons. What would they know of mass transit access to public beaches? To demontrate the opposite ends of a gaping divide, those taking mass transit to the beach probably don’t often use the word “paradigmatic”, but they know how to read a bus schedule. Conversely, the “well educated” group offers commentary, but doesn’t even know that the bus or the schedule actually exist.

Mass Transit to Jones Beach from The Beginning

In 1930, its first full season, Jones Beach drew 1.75 million visitors when the population of New York City was 6.9 million, many of which were suffering the reverses of The Great Depression. It’s far more likely that a significant number of those visitors arrived by either taking the train to Wantagh and then a bus to the beach, or one of the express buses that ran from four different locations in Manhattan as well as from Flushing, Jamaica, and Astoria in Queens, and by 1931, Flatbush in Brooklyn.

Conclusions

What is most important in regard to Mr. Moses and his bridges is that state law prohibits trailers and commercial traffic on parkways. Because of this, it would be preposterous to expect Robert Moses to plan a road and its overpasses in order to, at some point in the distant future, or likely never, provide access to vehicles that are disallowed by statute. Although history has shown that Mr. Moses’ designs have been both flexible and expandable over time.

Circling back to Goebbels, he always believed that propaganda should be the truth. It just needed to be limited to only the portions that were most favorable to his desired position. In the case of the parkway bridges, it seems that this obvious and easily disproved fabrication wouldn’t even meet his partisan editorial standards.

Athough Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) originally published the general sentiment, in regard to Robert Moses, the Alamosa (Colo.) Journal probably put it most appropriately: “Once fairly on its feet, a good substantial lie about a man in public life, will circle the globe while a truth is lacing its shoes on.” https://quoteinvestigator.com/2014/07/13/truth/

Great article. The point that the “Goebbels quote” about repeating lies was a much repeated falsehood is indeed ironic. Also fascinating how it is so overlooked that clearance is greatest at the center of an arch. History of Bethpage Pkwy real interesting. Once false lore starts, like Moses’ alleged racist intents, it takes life of its own. Well done.

There is a detailed “Documentary” film about Robert Moses which also repeats the same “Racist Low Overpasses” lie. Sadly I believed that lie until I recently did some research after someone questioned US Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg when he repeated this “racist overpass”lie yesterday.

Yes, there were buses that went to Jones beach. They would go along local roads which made the trip much longer than it would have been by car. My elder had spoken so many times about how the bus her old man drove had a hard time getting permits to go to Jones Beach (most of the buses charted by black drivers had a hard time) getting off a bus at Jones beach meant walking through the parking areas and then to beaches that could not compare to the “beautiful” beaches she recalled seeing (because they swam where black lifeguards were on duty, the underdeveloped beaches) as they were discouraged from going to the beaches which were actually developed.

I hadn’t experienced it myself, but that’s a first hand encounter from someone who lived through it. The resort like experience was limited if you could not drive because the buses could only go but so far with their permits.

I’ve reviewed your post several times. There are a number of clarifications that I would like to address.

1) There were no “local roads” to the beach. Bear in mind that Jones Beach opened in 1929. If you were to view maps from that period, the overall road net of Long Island was far more limited than it is today. You don’t describe where your family departed from or by what means they travelled. Typically, the longest mass transit trips from Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens were no more than an hour and twenty minutes. More importantly the great majority of these borough residents (regardless of race) didn’t own cars.

2) In general, all private buses ‘had a hard time” getting permits for excursions. There were a significant number of bus lines that had paid for public transit access. Charter access was limited because charter buses required parking while mass transit lines would continuously circumnavigate their routes. By midday the contract buses would also need parking areas because they would park from roughly noon until two.

3) All public contract buses would drop off their passengers at the Central Mall, and the East and West Bathhouses. Those buses also transported whoever got on the bus (regardless of race). The Central Mall and bathhouses were the most “developed” areas of Jones Beach, so overall it would be difficult to segregate the park. Those three stops would also place people at the center of the park. I can’t tell you how often on a busy weekend summer day that my family (with a car) would have to walk at least, a half mile or more from the far end of parking field 4 to the beach.

4) From all sources and from personal experience, all of Jones Beach was “developed”. I’m unfamiliar with any idea that “black lifeguards” served on segregated beaches. My earliest memories stretch back to 1968 and I can assure you that as early that time, Jones Beach was fully integrated.

Just an awful read. Can’t believe you put a bunch of time into defending Moses. He was demonstrably racist, but even more so he was classist. CLASS divides have always been present in NYC. May have eluded you in your studies.

I always welcome opposing views, provided that they are factually supportable. I believe my other posts indicate that NYC and most of the country are significantly segregated areas.

Moses had nothing to do with this. Today, criticism is based on the idea that Moses segregated Long Island by building roads to divide people/neighborhoods, this is untrue specifically because these roads were built when most of the surrounding areas were agricultural. It wasn’t until elected officials, zoning boards, etc. determined development codes that segregation occurred. This is discussed in my “Protesting Robert Moses” article. I particularly cover the developments of the lawsuits concerning the segregation of Stuyvesant Town in my “Canceling Robert Moses” post.

I welcome any specific examples of Robert Moses being a “racist” or “classist”. Although I’ve often heard those accusations, I’ve yet to hear one that indicates this behavior on Moses’ part.