In November of 2019 Assemblyman Daniel J. O’Donnell, Chairmen of the New York Assembly’s Committee on Tourism, Parks, Arts, and Sports Development introduced Assembly bill A08740, “An act to establish a temporary state commission to rename Robert Moses State Park”. The justification for this bill contains a number of erroneous statements regarding Mr. Moses that have, over time, gone from the fringe to the mainstream.

It’s unfortunate that various journalists, professors, and politicians have chosen to repeat salacious fabrications and engage in groupthink without making some simple inquires in order to determine the validity of their assertions.

The purpose of this blog is to provide historically accurate information, for review and commentary, which will ultimately arrive at a fact-based portrayal of Robert Moses.

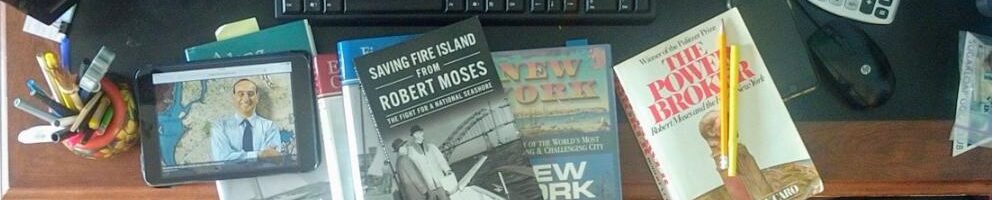

I had initially sent an email to Assemblyman O’Donnell and the members of his committee discussing A08740, I also forwarded it to a few local newspapers and reporters. I have yet to hear back from these entities in any substantive way. It appears that at this point, the best approach would be to start off this blog with this communication. Although, in the interest of full disclosure, I have made some minor revisions to the original, mostly a misplaced comma or word. I should also warn you that it is a bit long, but compared to “The Power Broker”, it’s a piece of cake. The email:

Sent: Monday, December 16, 2019, 01:04:32 PM EST

Subject: Lack of Justification for Proposed Renaming of RMSP

Assemblyman Daniel J. O’Donnell,

I recently read the justification for Bill # A08740, Titled “An act to establish a temporary state commission to rename the Robert Moses State Park.”

Unfortunately, the charges that you level against Mr. Moses are oft-repeated, yet regrettably groundless and to a great extent, historically inaccurate.

>Parkway Bridges

You state that “When Robert Moses helped construct Jones Beach State Park, he intentionally ordered the overpasses of the connecting parkway too low for buses, so that poor people, particularly African-American families, could not access the beach.” This statement is patently false. Buses have been able to access Jones Beach since it opened to the present day.

The Bee Line, bus company, made regular runs to Jones Beach on multiple routes. Buses to this day follow the same traffic pattern upon arriving at the beach. The first stop is the West Bathhouse, followed by The Central Mall, East Bathhouse, and a turnaround to stop at Zach’s Bay. This pattern was designed by Moses in order to accommodate bus bound travelers at the bathhouses so they could take advantage of the amenities such as showers, wringers to dry bathing suits, concessions, and lockers.

Robert Moses ensured that State Park literature made the public aware of this. Below is a 1930s postcard of the Central Mall. If you notice two buses are present at the traffic circle.

This is an article from the June 14, 1931 Brooklyn Daily Eagle describing the Bee Line bus route from Brooklyn to Jones Beach.

John Hanc in “Jones Beach: An Illustrated History”, provides the following description of the Park from an August 3, 1930, New York Times feature story by C. G. Poore.

“Poore expressed satisfaction with the cost of a day at the new beach, something that would no doubt have been a concern uppermost in the minds of many New Yorkers in 1930. He liked the fact that there were only two private concessions at the beach (the restaurant at the pavilion and what were called “the bathing accessories”). Everything else was run by the state, which in 1930 seemed almost a relief to beachgoers, who had probably been fleeced once too often by price gougers at private beaches.

Parking fees at Jones Beach were 25 cents on a weekday and 50 cents on Saturdays and Sundays. During the summer season, express buses to Jones Beach ran hourly from four locations in Manhattan as well as from Flushing, Jamaica, and Astoria in Queens. Visitors could also take the Long Island Rail Road from Brooklyn or Manhattan to Wantagh, and then board a bus to Jones Beach.

In an era when people came to the beach dressed in what we would now consider business or even formal attire, and then changed into their swimsuits, lockers were important. In its first full season, Jones Beach had plenty – 8,782 to be precise – at a cost of 35 cents per day’s rental. The cost to use one of the 809 private dressing rooms was 75 cents; you could rent a bathing suit for 50 cents and a towel for a dime.”

There was and still is a route that departs from the LIRR’s Freeport station to Jones Beach. Nassau Inter-County Express runs that route as well as one that runs from the Hicksville train Station.

Regarding the parkway bridges, particularly Southern State Parkway, is that when construction began in 1925 it was designed as a forty-two foot wide undivided roadway with two lanes in each direction. Since then, the road has been modified and widened in order to accommodate 190,000 daily trips on the Nassau County section. Since the bridges are arched, the extensive widening has led to a significantly lower height from pavement edge to bridge than the original design. http://www.nycroads.com/roads/southern/

>Pools & Parks

In regard to Moses role as Commissioner of the New York City Parks Department, you accuse him of building “most public parks, playgrounds, and pools far from Puerto Rican and African-American neighborhoods.” you further state that “one of the few times Moses did build a pool near a predominately African-American neighborhood in Harlem, he ordered it to be kept at a “deliberately icy” temperature based on his racist belief that this would keep African-American families away.”

According to the 1940 Census, the population of New York City totaled 7,454,995. The racial breakdown was 6,856,586 non-Hispanic white, 458,444 African-American, and 120,915 Hispanic/Latino. Respectively, these groups represented 91.97%, 6.15%, and 1.62% of the total population.

It would be understandable, based on the racial breakdown of the city in 1940, that the population disparity, would create more parks and pools in white communities. The Hispanic/Latino population at the time was small and scattered about the City. Puerto Ricans would have been an even smaller subset within this group. Frankly, if Mr. Moses had wished to discriminate against Puerto Ricans, he would have had to actively seek them out first.

Over 400,000 African-Americans lived in the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. They were a large and concentrated enough group to selectively discriminate against. The following map, illustrates that African-American neighborhoods could be easily avoided, especially in the case of the 11 large WPA pools that were opened in the summer of 1936.

Black Population Census 1940 REDISCOVERING ROBERT MOSES’S TRUE LEGACY HOW PLANNING BUILT THE PUBLIC CITY

Fortunately, the CUNYs Center For Urban Research has utilized a 1943 New York City Market Analysis that had been compiled by “The News”, “The New York Times”, “The Daily Mirror”, and “The Journal American” utilizing the 1940 Census. http://www.1940snewyork.com/

The Analysis broke the City up into 116 neighborhoods. Each of these area profiles contain a map, photos, economic factors, racial mix, and a brief description. As a result, it is possible to view the information for each neighborhood where a pool was sited and determine their respective African American populations.

(Listed in order of opening)Astoria – 81, Hamilton Fish – 1,800, Betsy Head – 12,638, Highbridge – 2,653, Thomas Jefferson – 25,345, Joseph H. Lyons – 497, McCarren – 3,298, Red Hook – 2,444, Colonial (Jackie Robinson) – 37,981, Sunset – 30.

The list totals almost 87,000. While the black population of New York City was 6.2%, nearly 19% of that population had pools sited in their neighborhoods. This would imply that Robert Moses actually made an effort to provide greater minority access to these facilities. If the pools were placed equally, based on representative population, this number would have been closer to 28,000. A number lower than this would indicate a policy of discrimination.

It’s important to understand that these facilities were also designed for year round use. In the cooler months the pools would be drained and used for various outdoor recreations such as shuffleboard etc. and the locker areas would be converted for indoor activities such as basketball. Which provided the surrounding communities with ample recreational opportunities.

This brings us to one of the most ignorant and meanspirited accusations, that Robert Moses purposely kept the pools in minority neighborhoods “icy” because of his racist beliefs that African-Americans could not tolerate cold water as easily as whites, and as a result, they would stay away. This is uniquely repugnant because it is so easily dispelled, yet disgusting that people would propagate this obvious falsehood.

New York City’s water comes from it’s Croton and Catskill/Delaware Reservoir system. Since these are surface waters, their temperature varies with the seasons. According to the NYC DEP 2018 Water quality report, 16,034 samples indicated a temperature range of 33 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit. In July and August, water entering the City from the supply system is almost 70 degrees. In order for Moses to keep any pools particularly “icy”, a separate refrigeration system would have needed to be constructed to chill the pool water. This system would need to be especially robust when considering that the source water is roughly seventy degrees, while at the same time, thousands of individuals, each with a body temperature above 98 degrees are in the water, while the daytime atmospheric temperature averages 80 degrees, and the sun often beats down on the entire facility. I am unaware of any such system being incorporated into the design of any of these pools.

It’s bad enough to consider that only a devout racist would conceive of the initial concept that black people are uniquely sensitive to cold water. But in order to propagate the myth of Mr. Moses perfidy, an individual would need to be ignorant of New York City’s infrastructure. They would also need to be devoid of any concepts of construction and maintenance budgets. Most likely they would also have an agenda to smear an individual while never making any attempt to determine the veracity of the accusation.

Moses clearly understood that funding for future projects was dependent on the success of his current projects. The ludicrous suggestion here, and in regard to bus access to Jones Beach is that he was so committed to a bigoted agenda that he would be willing to sabotage his own career by driving down attendance at his recreational facilities.

>Urban Renewal

As to Mr. Moses’ roles in urban renewal you charge that “Moses also pursued the systematic displacement and segregation of families of color in Manhattan and beyond: Moses helped displace over 7000 people, mainly of African-Americans and Puerto Ricans who lived in the historic and diverse neighborhood of San Juan Hill to build Lincoln Center, and revised language in a city contract that effectively allowed for the discrimination against black veterans and their families in the Stuyvesant Town development.”

In this section, it’s necessary to have an understanding of the evolution of housing laws that had been passed from the 1920s forward. These laws sought to bring private capital into “slum clearance” projects. New York’s insurance and banking industries particularly, were being courted as a source of funding. As in most interactions between government and moneyed interests, projects are often stymied or developed based on the will of the wealthy. The primary enticements to these interests came in the form of tax exemptions and the exercise of eminent domain powers.

In 1941, the New York Legislature passed the Urban Redevelopment Corporations Law, which allowed for tax exemptions and eminent domain, but also required that local planning commissions approve redevelopment plans and that the plans provided for tenant relocation. The following year, the legislature passed the Redevelopment Companies Law, which offered further inducements. When this failed to attract the interest of the redevelopment companies, a set of amendments to this law were created which eliminated tenant relocation requirements, reduced the oversight of planning commissions, determined that condemnation could occur for a “superior public use”, and made allowances to avoid rent restrictions. Although Governor Dewey held some reservation about these amendments, he signed them into law and pronounced his view that it came down to a matter of “housing or no housing.”

Although the chairman of Metropolitan Life had previously told the New York Times that Stuyvesant Town would only accept white tenants, both the City Planning Commission and the Board of Estimate voted to approve the project.

The first discrimination lawsuit concerning this project was filed in 1944, Pratt v. LaGuardia. The plaintiffs argued that public assistance for the project such as tax exemptions and eminent domain, would disallow Metropolitan from enacting discrimination policies. The case lost initially and on appeal because the courts held that since the project hadn’t yet been built, no one had been discriminated against.

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town, was brought in 1946. Three African American WWII veterans were not accepted as tenants because of their race. Metropolitan admitted to discrimination, but argued that, like any private landlord, they could accept or disallow whichever tenants they wished to. The court ruled that once the property had been sold to Metropolitan and the project completed, that the public purpose of the project was completed and the owner was a private entity. The case went to the Appellate Division and then the Appeals Court. The legal arguments advanced were substantial. While the initial suit was put forth by the ACLU, the NAACP was now involved on appeal being represented by future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. Both Courts found for Metropolitan. The plaintiffs then submitted a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court. In June of 1950 the court denied the writ, meaning that the New York Appeals Court decision would stand.

It would appear, based on this set of facts, that far more took place than “revised language in a city contract”. To believe that Robert Moses influenced the outcome of a discrimination policy at Stuyvesant Town would mean that he had the power to bend the City Boards, The Mayor, The State Legislature, The Governor, The New York State Supreme, Appellate, and Appeals Courts, and the United States Supreme Court, to his will. Only a neophyte to the concepts of representational democracy would think that he could alter contracts without oversight, and as a result establish housing policy.

Incidentally, the noted Progressive Samuel Seabury who fought against Tammany Hall’s dominance of New York politics and also presided over the Seabury Hearings which investigated corruption in New York City’s municipal courts and police department, and ultimately forced Mayor Jimmy Walker out of office, served as Lead Council for Metropolitan Life in Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town. His representation had far more to do with the discrimination policy at Stuyvesant Town than Robert Moses did. It turns out there is a park named for him at 96th and Lexington. https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/samuel-seabury-playground/history

As for San Juan Hill, according to the 1940 census, the area from 42nd to 70th and from Amsterdam Avenue to the Hudson River is known as DeWitt Clinton. The African American population is listed as 3,481. The physical site of Lincoln Center places it as part of the Columbus Circle neighborhood, with a black population of 1,991.

The 2010 census shows that this area is now divided into MN14 (Lincoln Square), and MN15 (Clinton) the black population of these two areas totals 5,579. While the Hispanic population, which was negligible in 1940, totals 14,194. It would appear that these minority populations are flourishing in these areas today. The question remains what factors brought about this result. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/data-maps/nyc-population/census2010/t_pl_p3a_nta.pdf

Map of Upper West Side urban renewal and public housing projects from West Side Urban Renewal Area preliminary plan, 1959 | Image via Michael MinnFrom: “The scythe of progress must move northward”: Urban Renewal on the Upper West Side | Urban Omnibus

Urban infrastructure which contains affordable housing combined with recreational facilities and cultural institutions tend to become particularly desirable. Much of the west side of these districts through the 1930s was dominated by commercial uses. While many changes have occurred in this area between then and now, much of the underpinnings which made that change possible were either through the direct actions of Mr. Moses or later efforts which built upon the foundations he created. Unfortunately, Robert Moses is an easy target because he was the one who initiated these changes, yet he receives little to no credit for the outcome.

After he had retired, when confronted by the barbs of detractors, Moses responded that, “Anyone in public works is bound to be a target of arbitrary administration and power broking levelled by critics who never had responsibility for building anything. I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without moving people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs.”

>Conclusions

For far too long in the public square, there has been a growing contempt of Robert Moses. Many of the accusations are the same as those contained in the justification for this proposed bill to rename Robert Moses State Park. As this essay shows, these accusations are baseless and without merit. Unfortunately, our society also seems to be moving in a direction where moral outrage eclipses thoughtful scrutiny. Where ego upstages ethics, and a loudly yelled uninformed opinion carries more weight than a deliberate, well-developed viewpoint based on facts.

Over this time I would often hear attacks against Bob Moses parroted by some overindulged PhD, from some Ivy League or other rarified institution, where compensation is based on abstract thought rather than actual results. It never mattered much because my view was that the individual was speaking from a place of ignorance, which was only cultivated through speaking extensively with other “experts” who shared the same perspective. Moses seemed to see this trend developing when he said “What with poisonous critics, savage commentators, public relations advisors, speech and ghost writers and equal time rebuttal spouters over the air, we are rapidly succumbing to what Whitney Griswold of Yale used to aptly call “nothing but technological illiteracy”.”

After I read “The Powerbroker”, I often wondered how in seven years of research, resulting in a biography which included eighty-three pages of notes gleaned from five hundred and twenty two separate interviews, Mr. Caro never seemed to find the time to consult a bus schedule to see how the other half got to Jones Beach. But then I came across an interview with Mr. Caro from Esquire Magazine where he described his process of writing a book. “Caro knits together his fingers until he knows what his book is about. Once he is certain, he will write one or two paragraphs – he aims for one, but usually writes two, ..that capture his ambitions. Those two paragraphs will be his guide for as long as he’s working on the book. Whenever he feels lost, whenever he finds himself buried in research or dropping the thread….he can read those two paragraphs back to himself and find anchor again.” In regard to “The Powerbroker” he had come up with the final line in 1967, “Why weren’t they grateful?”. Once he arrived at the conclusion, he states in the interview “All of a sudden, I knew what the book was, so with every book, I have to write the last line.” https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/books/a13522/robert-caro-0512/

This may be a great approach for a writer of fiction, but no historian worth their salt would work backwards from a preconceived conclusion. First they would extensively study the subject, and after considering all relevant facts, would then arrive at a determination of a supportable narrative. The greatest danger in Mr. Caro’s process, is that it would create an environment where evidence that would contravene the predetermined portrayal would be either discounted or discarded.

This matter became actionable to me once these misguided views went from the domain of uninformed elitists to potentially becoming a law drafted by an institution funded by the taxpayers of this State. All citizens have a duty to ensure that our political leaders understand that laws need to be based on facts, as opposed to grandstanding efforts to gain political capital by painting a hard working, dedicated public servant, as a racist deserving of erasure from the achievements that are his legacy through smears, innuendo, and outright lies. I submit that purely based on the attendance figures and uses of Jones Beach, Robert Moses State Park, The WPA pools, Shea Stadium, The 1939 and 1964 World Fairs, housing developments, bridges & tunnels the parkways and roadways, among all of the other infrastructure too lengthy to list, that no one in history has done more to bring together people of all stripes by constructing the public venues and routes to access them than Bob Moses.

I request that based on the issues raised in this missive, you withdraw Bill A08740 for lack of foundational justification.

Moses ran roughshod over neighborhoods that stood in the way of his plans. It didn’t matter if they were black or white, as evidenced by the Cross-Bronx Expressway and the Narrows Bridge and his plan to destroy Brooklyn Heights, only thwarted by Eleanor Roosevelt. His parkway scheme also grabbed property from the rich, the Belmont estate for one, if memory of “The Power Broker” serves me right. His accomplishments were considerable, but he stayed too long and thought God had given him the Ten Commandments. Those who paint him as a racist are guilty of the logical fallacy of presentism, judging the past by their own standards, which given their remarks are low.